A drone battery pack rarely “fails early” because one number on the label was wrong. In most industrial UAV programs, early failure is the result of small engineering assumptions stacking up—peak current margins that were never measured, thermal paths that were “good enough” in a prototype, or acceptance criteria that didn’t reflect real duty cycles. In many industrial UAV programs, early failure in a lithium battery pack is not caused by a single defective cell, but by how peak load, heat, and voltage behavior interact over time. The cost shows up later as shorter endurance than expected, rising voltage sag, unstable pack behavior across a fleet, and replacement cycles that become hard to predict.

This guide breaks down six common engineering mistakes that push drone battery packs toward premature performance loss—and what you can do at the system level to prevent them.

What “Fail Early” Usually Looks Like in Real UAV Operations

Early failure is often gradual, not dramatic. You may see:

- Endurance dropping faster than planned, especially under load

- Low-voltage warnings appearing earlier in the mission

- Packs running noticeably warmer at the same payload and weather

- Wider spread in performance between packs from the same batch

- Balance drift that gets harder to correct over time

These symptoms usually point to system-level stress and consistency issues rather than a single defective cell.

Mistake 1: Designing for Nominal Load Instead of Peak Load

Many UAV power profiles are defined by bursts: takeoff, aggressive climbs, wind correction, payload activation, and rapid throttle transitions. If your pack is designed around “average current,” you can still be under-protected at the moments that matter most.

What goes wrong

- Peak current spikes cause deeper voltage sag than expected

- Heat rises quickly in connectors, tabs, and internal paths

- Protection thresholds may be triggered earlier, shrinking usable energy

What to do

- Define peak current and duration as a requirement, not a guess

- Validate with real mission profiles, not only bench curves

- Leave margin for aging: internal resistance rises with cycles

Many standard battery tests are performed under steady conditions and fail to capture current spikes and enclosure heat seen in real UAV missions.

Mistake 2: Treating Voltage Architecture as a Battery Decision, Not a System Decision

You can’t fix a system mismatch by swapping packs. Voltage architecture controls current, wiring loss, ESC thermal stress, and how voltage thresholds behave under load. When the architecture is wrong, a “bigger battery” just hides the issue temporarily.

If you need a structured way to align voltage selection with endurance goals and integration constraints, start from 6S, 7S, and 12S battery pack selection.

What goes wrong

- Higher current than expected accelerates heat and aging

- Voltage thresholds trigger early under dynamic loads

- ESC and wiring run close to limits, reducing lifespan

What to do

- Choose architecture based on real load and thermal constraints

- Validate endurance as “usable energy under load,” not nominal capacit

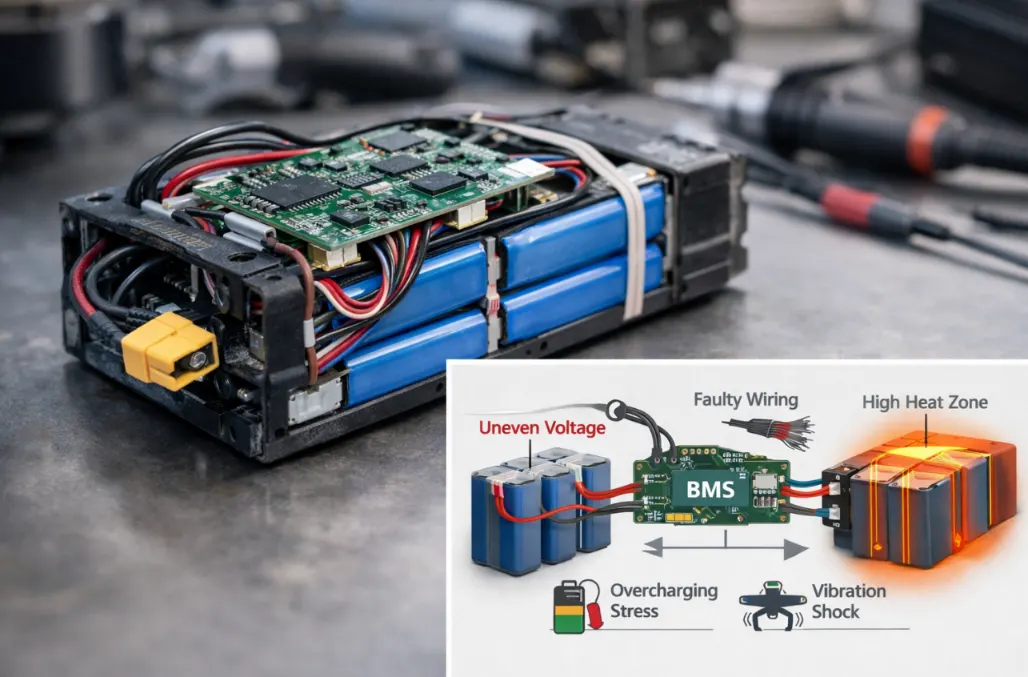

- Consider wiring and connector losses as part of your energy budgetWhile the battery management system (BMS) plays an important protective role, most premature battery failures originate from system-level load and thermal decisions rather than BMS logic itself.

Mistake 3: Underestimating Thermal Reality Inside the Airframe

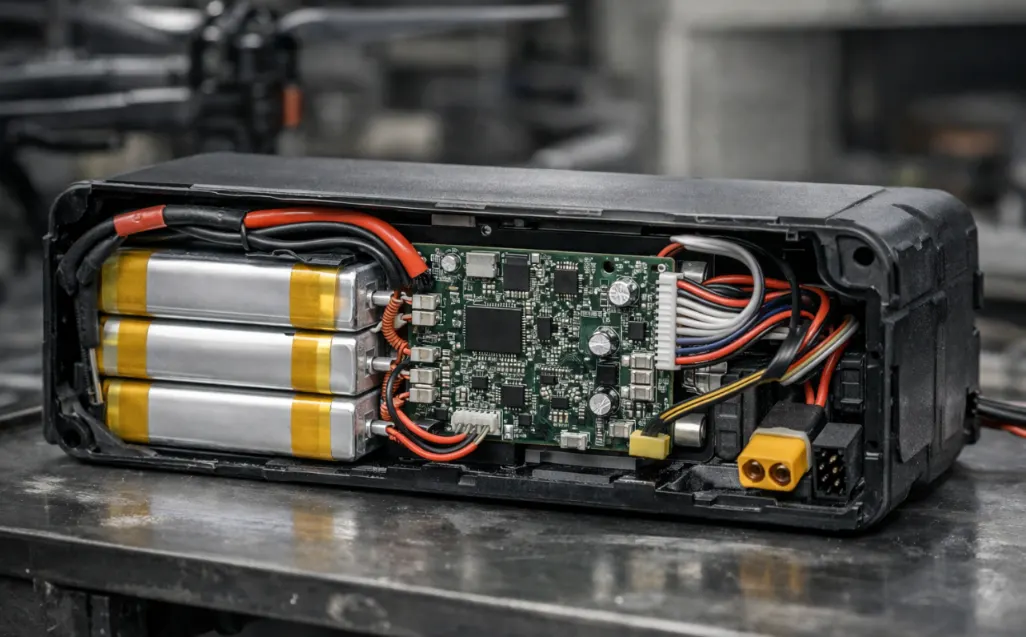

Batteries don’t fail in open air—they fail inside enclosures. Airflow, shielding, proximity to motors/ESCs, and installation orientation all change thermal behavior. Packs that look stable on a bench can degrade quickly in the airframe.

What goes wrong

- Hot spots form near connectors and current paths

- Thermal cycling accelerates resistance growth

- Packs become more sensitive to aggressive charging and deep discharge

What to do

- Validate temperature at the pack, connectors, and nearby components

- Define a max operating temperature limit and enforce it

- Improve thermal paths before “upgrading” capacity

Mistake 4: Accepting Batch Variation Without a Clear Consistency Spec

Fleet operations amplify small differences. If batch-to-batch matching is loose, you may see one pack sag earlier, one pack drift in balance faster, and one pack degrade noticeably sooner. That is a planning problem, not just a quality nuisance.

What goes wrong

- Wide spread in voltage curves and internal resistance

- Unpredictable endurance across aircraft

- Maintenance becomes reactive instead of planned

What to do

- Define acceptance criteria beyond capacity (e.g., IR bands, voltage curve behavior)

- Require consistent test methods and reporting

- Track performance drift at the fleet level, not pack-by-pack anecdotes

Mistake 5: Building “Custom” Packs Without Defining the Discharge Profile

A pack can be “custom voltage” and still fail early if it’s not designed around your mission’s discharge pattern and thermal window. In 2026 and beyond, custom battery work is shifting from “series count” to “load profile design.”

What goes wrong

- Packs are overbuilt in capacity but underbuilt in current path stability

- Design assumptions don’t match peak vs sustained current reality

- Packs age faster because heat rises where you didn’t model it

What to do

- Write requirements for peak current, sustained current, and temperature window

- Validate the full mission profile before scaling production

- Treat the pack as part of the powertrain, not an interchangeable module

If you’re benchmarking what “field-ready” pack engineering looks like for your sector, reviewing industrial drone battery solutions can help you set realistic requirements and avoid spec-only decisions.

Mistake 6: Letting Charging and Storage Strategy Be “Operator Dependent”

Early failure often accelerates when charging is inconsistent—especially when field operators are under time pressure. Fast charging, charging while warm, storing fully charged for long periods, or pushing deep discharge repeatedly can all shorten usable lifespan.

What goes wrong

- Resistance increases faster than planned

- Voltage sag worsens, reducing usable energy

- Balance drift becomes more frequent

What to do

- Define charging rules that match real field behavior

- Set storage voltage targets and enforce them operationally

- Monitor pack temperature before and during charging

Quick Diagnostic Table: Symptom → Likely Cause → Practical Fix

| Symptom in the field | Most likely underlying cause | Practical fix direction |

|---|---|---|

| Endurance drops quickly after a few dozen cycles | Heat + high peak load margin too tight | Reduce peak stress, improve thermal path, add margin |

| Low-voltage warnings appear early | Voltage sag from rising resistance | Validate under real load, tighten consistency specs |

| Packs vary widely in flight time | Batch inconsistency or mixed aging | Define acceptance criteria, track fleet-level drift |

| Packs run hotter than expected | Enclosure airflow and connector losses | Measure hot spots, upgrade wiring/connectors, re-route airflow |

| Balance drift increases over time | Cell mismatch + stressful duty cycles | Improve matching, adjust charging/storage habits |

Conclusion

Drone battery packs usually fail early for predictable reasons: peak load was underestimated, thermal behavior wasn’t validated in the final airframe, consistency requirements were too loose, and “custom” meant voltage only instead of mission-defined discharge behavior. In 2026, OEM teams that treat the battery as a system component—validated against real load, heat, and fleet consistency targets—will achieve longer usable lifespan and more predictable operations.

In practice, early battery failure is rarely a question of choosing the “wrong” battery manufacturer, but of defining realistic requirements and validating them at the system level.

Shengya Electronic: A System-Level Approach to Pack Reliability

In real UAV programs, battery performance is rarely determined by a single feature. It depends on how voltage, load, heat, and lifecycle expectations interact once a platform moves into routine operations. Shengya Electronic supports OEM teams at this system level, helping translate mission requirements into battery pack designs that remain stable under real operating conditions. Rather than optimizing for headline specifications, Shengya focuses on repeatable performance, controlled variation, and validation methods that reduce surprises once platforms scale into regular service.

FAQ

Q1:What does “battery pack fails early” usually mean in drones? ,A:It usually means faster voltage sag, reduced usable endurance, and inconsistent performance long before a pack becomes unusable.

Q2:Why does endurance drop even when capacity seems similar? ,A:Usable energy shrinks when voltage sags under load and triggers early cutoffs, often driven by rising internal resistance and heat.

Q3:What is the most common OEM engineering mistake? ,A:Designing for nominal current instead of peak load events during takeoff, wind correction, and payload transitions.

Q4:How do fleets reduce battery failures at scale? ,A:Set clear consistency specs (not just capacity), validate heat in the final enclosure, and test packs under real mission profiles.

Q5:What should “custom drone battery” mean in 2026? ,A:A pack designed around your discharge profile, thermal window, and lifecycle targets—not just a different voltage or capacity.